1

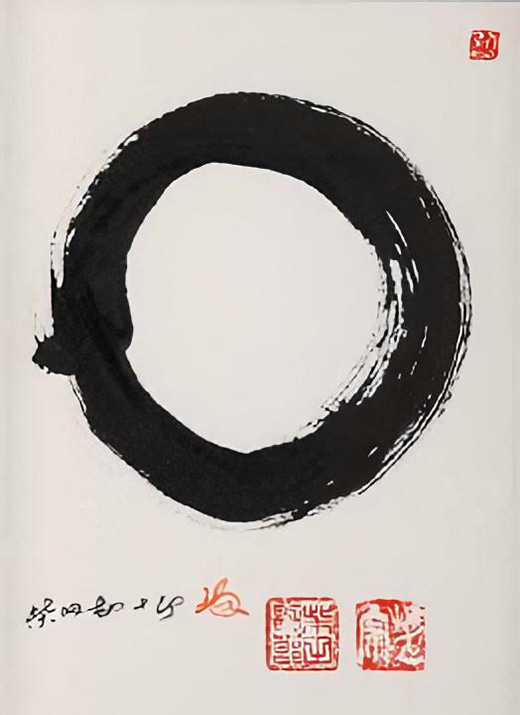

Some of my regular readers may have noticed that I recently changed the avatar of my Substack. The new image is an Enso, a symbol of great significance in Taoism and in Japanese Sumi-e painting. A wealth of meanings can be read into it; it can be seen as the circle of life or as the connectedness of all existence, or as the interplay of presence and absence, of emptiness and fulness. Ultimately it can be taken to represent infinity, the perfect meditative state, and hence Satori or enlightenment.

When contemplating an Enso it becomes evident that the form of the circle and the void it contains are interdependent and define each other, as in the famous pronouncement of the Heart Sutra, “form is void, void is form”. The circle can be open or closed; an open circle suggests movement and development as well as the imperfection of all things, hence a process of becoming, in the terms of a Western philosophical outlook. A closed circle represents perfection, stillness, or a state of being, paralleled again in Western thought by the ideal forms of Plato.

The Enso I have chosen for my Substack was painted by one of the outstanding Western exponents of Sumi-e, the Venezuelan artist and writer María Eugenia Manrique, who has kindly allowed me to reproduce it here. I felt it was particularly fitting for this purpose, for it is an unusually dynamic representation of this archetypal form, seeming almost to explode at the beginning and end of its trajectory into a chaotic exuberance.

All living things follow something like the cyclical pattern that the form of the Enso represents. This is evident in plants as in animals, yet when it comes to us humans the situation is more paradoxical. For while in our biological aspect we do indeed live out a life cycle, we experience the living of it very much as a timeline. This is as true for us as individuals, concerned as we are with our personal progress through life, as it is for our collective being, expressed in the strivings and confusions of historical development. It is as though we were trying to head off at a tangent from the life cycle towards some boundless future, yet sooner or later the cycle reasserts itself, pulling us back and ultimately down to the ground out of which we arose.

This implicit tension between cyclicity and linearity is evident in different ways at every stage of life. At the height of adulthood we tend to be absorbed in our own forward momentum, such as it is, as though it were going to continue indefinitely, even though we know it won’t. As we grow towards the helplessness of old age, however, we find ourselves recapitulating our original helplessness as children, and as babies and infants if it comes to that, before eventually being laid back in the earth-womb whence we emerged.

We can see here part of the reason why we are so enamoured of linearity, and why the cyclical pattern of nature tends not to appeal to us, reminding us, as it does, of our own mortality. This reluctance to acknowledge our cyclicity will be more pronounced the more we are absorbed in phenomenal existence; which means, expressed in terms of the Enso, the more we move exclusively through the unfolding circumference of life, having forgotten the void out of which it all arises. Thus we end up lacking the kind of perspective on the greater whole which still came naturally to people in traditional societies, enabling them to see not only their lives but their deaths also as part of the integrative process of all existence.

When we look at an Enso our attention will likely be attracted first to the trace of the circle; only on contemplating it further do we begin to sense that the image comprises equally the blank space contained within itself. If you consider again the image above but focus instead on the void of its inner space you may feel how the perspective changes, and as it does so, the inner and outer relate to each other in a different way. Likewise each individual life is not merely a form of embodiment on its own unique trajectory, call it a life cycle or a timeline as you prefer. It is also a manifestation of the unmanifest, of the one unchanging life which is prior to its manifold expressions, and yet which nourishes unstintingly the whole.

The void, or mu in Zen terminology, is contained within the circle, but also it is the precondition for the latter’s appearance. Mu is given form by the circle, and in that sense seems to be its predicate; yet in another way, the form could not have taken shape without the preexistence of mu, symbolised in this instance by the blank sheet of paper. That fertile blankness will remain on the disappearance of any and all particular expressions of the potentiality arising within itself. As Rumi puts it, “everything one sees has its roots in the unseen. The forms may change, yet the unseen essence remains the same.”

One further reading suggested to me by the Enso is that of the phenomenal, the outward trace, coiling about itself as it seeks the essential which it cannot grasp. Life can be a beautiful play of the particularity of forms, as we see in the natural world; but with the arrival on the scene of man, there arises also that reflexive consciousness which seeks to comprehend the nature of life, rather than simply living it. But form cannot comprehend the formless, and if it insists on attempting to do so it will only end up chasing its own tail, which would be another way of viewing the Enso in its open or incomplete variant.

Much of the happiness or misery we experience in life derives from our attitude to the formless, since it is this that we are forever pursuing, knowingly or otherwise, as it plays itself out through the medium of form. Should we be driven by an energy of grasping or appropriation we are fairly condemning ourselves to frustration, for we will end up with our hands full of nothing, having found the formless to be devoid of substance. For in its boundless nature it is not something we can ever have, as a possession, but only what we can be. And we can be it because we are it already; because we are the void out of which all manifestation arises, since the one in truth is inseparable from the other.

Inseparable in essence, separated in appearance. And having once assumed the guise of separation, form begins its interplay with the formless. One of the conditions of that interplay is that every form that emerges into being must have an ending also. This is obvious enough for most things, but when it comes to that vast ensemble which we call the world - our world - we baulk at the habitual conclusion.

Instead we assume that the world could go on more or less indefinitely, assuming that it could be managed in what we call a “sustainable” manner. But what if the human stewardship of the world had a fatal flaw from the outset? Then sooner or later its consequences would become manifest, ensuring that the great curving arc of our collective existence would recapitulate the course of everything else on Earth, and itself go down in turn towards dissolution.

2

One of the key differences between Eastern and Western spirituality is in their relationship to time. The spirituality of the East counterposes time to the timeless, and privileges the latter over the former. Time is tainted by Maya, illusion, and while it obviously needs to be dealt with on a daily basis, it can only ever lead us round and about our indwelling timeless nature, but can never take us directly to it. At most it is acknowledged that it may “take time” to recognise the inherent timelessness of that nature - one of those paradoxes in which spiritual teaching abounds.

The picture is rather different when we come to the Judeo-Christian view, a hyphenated term that finds justification precisely where the question of time is concerned. For the Christian understanding of the matter can be seen to blossom forth out of the Judaic, since what they have in common is an acute sense of specific and unique occurrences that reorientate the course of history. This is implicit at a number of points in the Hebrew Bible, such as the account of the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt.

The mythic religion which held sway in the Land of the Pharaohs was wedded to the cyclicities of nature, as were the religions of Canaan and Mesopotamia or indeed just about everywhere else in the ancient world at that time. By contrast the foundational event of what would eventually become Judaism was a breaking out of the cyclical order, and a long journey into the unknown, in quest of the Promised Land.

Indications of the Exodus in contemporary sources are few and doubtful, yet it is already implicitly an historical event in the sense that it records a singularity which was to change everything for the people involved in it. But it was by no means the only such singularity recorded in the Hebrew Bible. Another was the conquest of the kingdom of Judea by the Babylonians and the destruction of the first Temple of Jerusalem, which unlike the Exodus from Egypt is already a definite historical event, occurring in 586 BC.

Most conquered peoples in Antiquity lost their own gods on being reduced to servitude, and were assimilated to the religion of their new rulers. The Jews of the Babylonian exile, however, held fast to their faith, and through that fidelity developed a notion of endurance over time which was eventually vindicated by their deliverance from captivity. This notion of a long-suffering endurance ending in a Messianic age was carried over into Christianity, especially once early hopes of a swift return of Christ were disappointed. What developed instead was a vision of history stretching ahead indefinitely, reformulating as it did so the old cyclical notions current in the surrounding pagan culture.

Strengthening this linear view was the unknowable time of the Saviour’s return, often alluded to by Jesus in the Gospels. This represents a further break with the familiar periodicity of the old cyclical order, knowable because predictable like the seasons of which it was comprised. And yet the transition to a linear outlook is a complex one, for there were still definite cyclical elements both in the Jewish and Christian outlook. Taking again the example of the Babylonian Captivity, it was seen by the Jews as constituting in some respects a reenactment of the trials undergone during the wanderings in the desert at the time of Moses. Subsequently, and following a similar logic, much of the Hebrew Bible - or the Old Testament, as it would come to be called by Christians - came to be understood as a prefigurement of events in the life of Christ, or in the trials and progress of his Church.

But prefigurement and reenactment presuppose recurrent patterns, and suggest in turn the persistence of a modified cyclical understanding even in the midst of a broader linear unfolding. And in any case even the commemoration of the singular events which constitute the landmarks of the Jewish and Christian calendars - Passover, Christmas, Easter and so on - necessarily recur on an annual basis.

Ultimately the Christian vision, like the Jewish before it, can be seen as a blending of cyclical and linear aspects. The “last days” prefigured by the Book of Revelation suggest the end and hence also the accomplishment of a linear trajectory, yet it is just here where the cyclical aspect also comes to the fore. “I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the ending, saith the Lord, which is, and which was, and which is to come, the Almighty.” Alpha and Omega being the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, they represent together a coming round to “full circle”, hence the consummation of the ending in the beginning. But also “which is, and which was, and which is to come” indicates the timeless beyond time, that out of which time arises, and with it the totality of the manifest Universe.

3

The powerful and imposing language of Revelation seems to be far removed from the quiet suggestiveness of the Enso, that symbol of the cycle of life coming round in its own way towards completion. Yet we should not be surprised at such widely divergent symbolism; after all, each tradition is seeking to express something that in its vastness may be beyond what is possible to encapsulate fully from any single perspective.

In any case it is not surprising that Christianity and the Eastern religions should have different views of how the world will cease to be, given their divergent understanding of how the world is in the first place. For Christianity the world is real, being God-created, albeit fallen from its initial blessed state. This would suggest that the end of the world must be a tremendous occurrence, just as its Creation was awe-inspiring, or would have been if it had human witnesses. For Eastern spirituality, however, the reality status of the world is doubtful to say the least, being more like a plausible and absorbing dream, destined to dissolve into what the Hindus call pralaya, a kind of cosmic deep sleep, before arising again in a new form.

We can see how aspects of both of these visions are being borne out at the present time. In its incoherence and absurdity, as in its increasingly ephemeral and virtualised character, the world is obeying a trajectory similar to what an Eastern view might have envisaged, making it seem like a confused dream dissolving into imminent darkness. On the other hand the unleashing on an unprecedented scale of the forces of evil, depravity and corruption lends our times an apocalyptic character more in keeping with the dramatic symbolism of the Book of Revelation.

Neither of these views, however, is likely to exercise much hold over us for as long as we understand the passage of time in exclusively linear terms. In such an understanding time is an abstract quantity proceeding always straight ahead; however variable the faces of historical occurrence, time itself remains constant, untouched by what it measures. This holds true for the collective as for the individual case: even if we acknowledge that our own personal life describes a curve of sorts, rising in youth and declining with age, that curve is set off against the general course of things that continues on a linear axis. From this linearity we will eventually slip down to our individual fate, yet the axis itself is assumed to continue regardless.

Given such an understanding, any possible ending of the world would no longer be implicit in its beginning, nor would such an ending have any quality of consummation, as it does in the cyclical outlook. Instead a world’s end scenario would be bound to have a fortuitous character, being the outcome of unconscionable human folly or of a random event such as an asteroid strike.

The linear assumption - the linear prejudice as I am more inclined to call it - shapes our view of time and futurity profoundly, yet since it is taken mainly for granted it exerts its influence in quite an unconscious way. But we are touching here on a large theme that cannot adequately be addressed at the tail end of our present subject, and so it will have to be adjourned to a follow-up post for further exploration.