Posture as Metaphor

We can remain balanced and composed, even in the face of an imbalanced and decomposing world.

1

Depression has become a major issue in recent years given its increasing prevalence, especially among the young. Yet it is rarely related to physical posture, even though that too has been getting worse throughout the population for quite some time. This is a curious oversight, because the two things are easily correlated. We surely know from our own experience that we tend to sag and become disjointed physically when our spirits are low, while being inclined to straighten up and grow more integrated when in an upbeat mood. Good posture thus supports a positive outlook as much as bad posture undermines it.

Why then do we so rarely draw the connection between the two? One likely reason is that we are rarely alerted to the importance of good posture, and so are likely to miss its impact on our psychological wellbeing. It’s also the case that postural trends are very much collective in nature, changing only gradually over time, and hence easily missed by an attention focused on more immediate events. That is why it can be useful to check out street scene videos, easily found now on YouTube, from a century ago or more, and notice the rather striking differences between then and now so far as people’s posture and general bearing are concerned.

I’m not suggesting that everyone’s posture here is ideal, but by and large the contrast with a street scene today is pretty striking. There is a sense of self quite different then from now, expressed most obviously in the care with which people dress, and more subtly, in their self-possessed and purposeful bearing as they go about their business. Checking out other videos from Paris, London, Berlin and so on from around the same epoch, the impression is broadly similar.

Turning back to the present we find a commonly cited culprit for our posture woes: digital devices in general, and smartphones in particular. And certainly it’s true that many of us, probably most of us, have to spend hours every day “hunched over a computer”, and that “text neck” has become a common affliction among habitual smartphone users. Having said that, my sense of the matter is that the sudden ubiquity of screens in our lives only accentuated a trend which was already in evidence before that.

One indication of a decline predating the digital revolution can be detected through our changing notions of human anatomy. Posture expert Esther Gokhale has drawn attention to this fact, setting a “normal” spine from a 1990 textbook side by side with the image of a spine from (again) 1911. She argues persuasively that healthy posture is built around a J-shaped spine (below, right) rather than the S-shaped spine that has become predominant in recent decades (left).

Here we have a striking instance of how general practice comes to be reflected in established norms as set forth by experts and specialists, with those norms then affecting predominant habits in a feedback loop - a negative one in this instance. Thus an S-shaped spine has come to be the accepted standard in ergonomic design, for example, especially where seating is concerned. Note the typical curved back of the office chair in the image below, with the lumbar support brought unnaturally forward. This kind of support accentuates the S of the spine even beyond what today is considered normal, providing a striking example of expert misguidance embodied in a highly elaborate sitting contraption. (Incidentally the image is taken from an online article extolling the benefits of such contraptions. Amazing how our upright forbears managed to do without them!)

Bear in mind that the anatomical textbook featuring the S-shaped spine dates from 34 years ago, which would support my suggestion that the trend towards poor posture was already in evidence prior to the advent of smartphones and laptops. Likewise “ergonomic” seating has quite a history behind it already. Furthermore, examination of video footage would suggest that there was indeed a slight decline in posture in the concluding decades of the 20th century, before becoming much more pronounced with the onset of the digital age.

2

The quality of one’s posture has an effect not just at the physical but also at the emotional level, transmitting an unconscious message to others as well as to oneself. Indeed the relationship between physical and moral qualities is embedded in our speech, common parlance being full of terms expressing the connection.

Take a word like upstanding. It has the primary meaning of standing up straight, but also by extension it has a definite moral overtone. The OED gives the sense, “of a person: honest, honourable, decent; responsible.” The opposite of being upstanding is being spineless, or having no back bone - again the physical and moral references overlap. Being spineless expresses itself as an unwillingness to stand up for oneself, and contrasts with a readiness to stand up and be counted. Young people as they enter adult life are expected at some point to stand on their own two feet, in a kind of recapitulation in social terms of the physical achievement of the toddler in maintaining upright posture.

Now here’s a question. Take a look at the two models of the spine pictured above, and ask yourself, would I be more likely to be upstanding and all those other good things on the physical basis of a J-spine or an S-spine?

It’s an important question to ask, especially when we’re being told that we shouldn't trouble ourselves about it. Take a recent article in The Guardian entitled “Is good posture overrated? Back to first principles on back pain”. The article is topped by a photo of three skeletons with the caption, “What posture should we hold our spinal muscles in? Straight, you might think. But this seems an odd idea, given that the spine is naturally curved like an S.”

Aha, there we go! None of the academics interviewed for the article demonstrates any historical awareness on the question, while the one historian consulted suggests, apparently in all seriousness, that the “stand up straight” idea might have derived from the military parade ground.

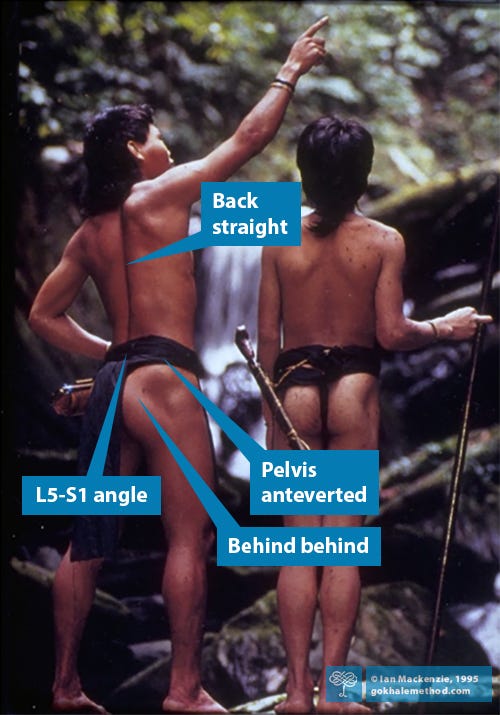

But this is a ludicrous notion. The superb posture of the Ubong tribesmen in the picture below (tags by Gokhale) was presumably not copied from any military exemplar. Instead it provides a splendid illustration of the kind of ancestral bearing to which we would all do well to aspire. And in any case military posture, with its stuck-out chest and general tension and rigidity, is not natural, and hence not sustainable either - which is why the parade-ground call to “attention!” is followed inevitably, and usually sooner rather than later, by the complementary command, “at ease!”

Sustainable posture, by contrast, is easeful at all times, for it promotes a natural tautness which is neither tight nor slack, and hence can be maintained for long periods of time without fatigue. Slouching on the other hand produces slackness in some parts of the body, obviously, but inevitably it also produces in other parts a compensating tightness. Hence the apparent paradox that someone who has spent time slumped on a sofa, for example, is bound to feel stiff when getting up from it.

One of the worthies interviewed in The Guardian article just mentioned opines that compared with “things that really make a difference, like depression and anxiety…the evidence suggests that posture just isn’t worth worrying about for most people”. And he adds, “I’m fairly slouched now - and I don’t worry about it.” Yes indeed, depression and anxiety “really make a difference”, not least to Big Pharma’s bottom line, constituting as they do a multi-billion dollar market, whereas postural re-education is, well, a zero-billion market for the drug producers.

No doubt it’s also just a coincidence that the billionaire who best represents the unlovely face of Pharma, Bill Gates, contributed a cool $13 million to The Guardian up to 2021. And Gates is well known for jealous oversight of any media coverage, especially related to health issues, which might have a bearing on his business dealings - sorry, his philanthropic concerns. Which certainly do not include concerns about healthy posture - especially as he’s a notorious sloucher himself.

3

We have already looked at some common phrases reflecting an overlap between physical and moral characteristics, and connected in some way with the spine. But there are many more relating to other parts of the body which likewise have a figurative sense. Think of “he hung his head in shame”, and consider what kind of message we are giving to ourselves and to others when a craned-forward head has become habitual with us - when we have adopted, in other words, a “hangdog” expression.

And speaking of dogs, think of the tucked pelvis which has also become habitual, inevitably, since it is the maladaptive complement to a craned-forward head. Remember the phrase, “he went away with his tail between his legs”? But that’s the way we look, and even more important, the way we are bound to feel, if only at an unconscious level, for as long as we have a tucked pelvis.

Then on top of that there is the small matter of excess weight and obesity, which have an impact on posture that ought to be obvious but is generally overlooked. Consider in this regard the phrase, “he can carry his weight”. What it indicates is a person who may be burdened with excess pounds or kilos, but whose underlying physical structure is sound, so that the weight is distributed and borne in an effective and relatively easeful manner. If you check out some of those street scenes on YouTube from a century ago or less, you may notice a few examples of the portly but upstanding gentleman or lady which will make my point succinctly.

Interestingly, it’s a long time since I’ve heard that phrase, “he can carry his weight”; I wonder if it would even be generally understood anymore. For while we have no shortage of people who are overweight in varying degrees, it’s rare to see someone whose underlying structure is such that the excess can be carried effectively. Instead the body is inclined to buckle or become splayed under the excess, maybe only slightly at first, but enough to set a damagingly maladaptive process in motion.

It is indeed remarkable that we should be so obsessed with weight, and at the same time so oblivious of the posture on which that weight must be distributed. Part of the reason for this, I would suggest, is that our general perception has been coarsened to the point where we tend to see only the gross in all things while missing the subtle. Bodily mass may be regarded as the gross factor in this context, bodily structure being in comparison relatively subtle.

I may have been giving the impression that we are all walking around like Quasimodo, in states of obvious deformity, but this is fortunately not the case. Some aspects of postural decay, it is true, can be fairly evident, such as humped shoulders and craned head; others such as tucked pelvis are less so. Or they are less so until one’s perception is attuned to noticing them. And of course there is also the factor of habituation: once tucked pelvis becomes the norm, as it has done over the last couple of decades, we simply don’t notice it anymore - especially if we are also doing it ourselves.

However there is another reason why we are focused so much on weight and so little on posture. For there is a tremendous and ever increasing bias in our contemporary mindset towards quantity and away from quality, and of course weight is readily quantifiable whereas posture is not. Not only does the latter elude quantification almost entirely, but even if it could be quantified in certain localised aspects, doing so would hardly serve much practical purpose.

As it happens, one of the frustrations expressed by the experts in that Guardian article is precisely this, that posture is so difficult to measure - another good reason, given the measurement obsession of scientific practice today, for simply disregarding it. After all, what possible significance can we attach to posture if it can be turned neither into data nor into dollars?

4

The qualitative wholeness of posture finds practical expression in the fact that it doesn’t lend itself to being worked on piecemeal and then assembled in a composite manner. But this is a tricky one, because certainly we will need to focus on particular parts of the body in the course of our postural reeducation; in doing so, however, we will also need to develop the awareness of how even quite small changes in one aspect will produce modifications elsewhere.

That means dispensing with any kind of robotic “body parts” approach, of the kind which unfortunately is evident in much of the health and fitness scene, as of course in conventional medicine also, from which presumably it derives. Effective work on posture will instead mean developing a sensitivity to how the part interacts with the whole and the whole in turn conditions each part, so that a localised focus can be integrated into the harmonised microcosm which the human body was always meant to be.

A body with good natural posture is very likely to be an integrated body, in two senses: integrated physically, as of the parts with the whole, but also integrated and harmonised with the non-physical, as the latter’s substantial expression in three-dimensional terms. In the absence of such integration we get what might be called the piled-up body, an easily toppled heap held together only by a weak and almost vestigial structure.

By contrast a body that is inspirited by a unified sense of itself will tend to be tautly vertical, not out of strain but out of easeful alertness, rather like an animal in the wild. Likewise its movement will be smooth and streamlined, whereas poor posture lacking in integration is bound to produce clumsy and mechanical motion. Instinctively we will expect more from someone with a body whose verticality is taut and alert than we would from someone with a piled-up body, each layer of which sits inertly atop the one below it.

Having said all that, it’s no simple matter to get back to healthy posture when the norm has already slid so far towards slouching and dis-integration. This is why a great deal of tolerance and understanding are required as we go about rectifying this unhappy situation. We need to know, furthermore, that it’s unlikely to be a quick fix, nor are quick fixes likely to help matters much. “Chest out, shoulders back” is the kind of peremptory instruction which has turned a lot of people off postural reeducation altogether, and not surprisingly. Try it and you’ll find that it’s simply unsustainable, for pulling and tugging at our bodies to make them fit a preconceived template is just not natural, and hence is likely to be followed by a further slump of discouragement.

In one way this “correct template” approach is the polar opposite of a complete disregard for posture expressed in slumping and slouching. Seen in another way, however, they reveal the same underlying prejudice about our physical nature. For what they have in common is the distorted belief that the body left to itself is just an insensate heap of matter. The sloucher accepts this belief and lets the body pile up on top of itself as habit may determine, whereas postural disciplinarians, if they still exist, seek to whip the inert heap of the body into a presentable shape, however misconceived. Both attitudes, however, are equally misinformed by a mechanistic view of the body which robs it of its innate wisdom.

Genuine postural reeducation is not about making the body do things, but about listening and being attentive to it, thereby learning what it would really like to do of its own accord. First though it will need to be freed from the mind-imposed habits that have twisted it out of its natural ease and harmony. Typically the sustained impact of those bad habits will have led the body to mistake good for bad and bad for good, feeling comfort as discomfort and vice versa. To that extent some gentle insistence will surely be necessary to free it of these long-established patterns.

However once it is no longer treated as an insensate machine and instead is encouraged to recover its own natural intelligence, the body will soon begin to show how exquisitely responsive it really is. More than that: it will reveal what it knows about itself and even about its own physical environment that the presumptuous mind does not and cannot know.

I said it’s not a quick fix, and that may seem like bad news, but really that’s not the case. For once the right guidance and a suitable form of practice are found, the way back to healthy and natural posture will be one of continuous revelation as we rediscover what a marvellous instrument we have at our disposal. Through this progressive rediscovery what will open up for us is a new attitude to life at its most immediate, physical level. This attitude will not be defensive and evasive, as with the sloucher, nor strained in an artificial pose, as with the “correct template” approach. Instead the attuned physical presence of natural posture can contribute to a genuine feeling of composure, grounding us in the face of a world gone dangerously adrift.

Interesting thoughts on when bad posture first set in. I associate it with Rock n roll, mid 70s, thereabouts. Being in school at the time, it was the cool thing to go around hunched-up, like your guitar hero. That was then compounded by the spread of left-wing politics and the sexual revolution: the older generation were stiff and up-tight and right-wing. The youth were laid-back and slack. So a lot of it was down to generational rebellion which then went on and on through the gens. Maybe Gen Z is the first that's showing signs of reaction. If they could only get off their phones!