On the Cusp of Dream and Waking

What we call objective reality begins anew for us each day, and ends each night. What if our whole world is facing a similar onset of night? What if we are nearing the end of our civilizational day?

1

We are all familiar, on waking in the morning, with that moment when the dream we were likely having is supplanted by our daytime world. Over the course of a lifetime it has occurred so often that we hardly notice it anymore. And even if we did, what could we say about it except that the unreality of dream has given way to the reality of the waking state? And since the waking state is there already waiting to make its demands on us, we had better be up and doing rather than pausing to ponder on the strangeness of the transition which has just occurred.

Dreams by their own nature contribute to this conditioned reflex, since they are elusive things that don’t seem to like daylight very much. But sometimes it happens that a dream makes an unusual impact on us, so that its distinctive feeling tone or some isolated scenes from it linger through the succeeding hours. Casting back to childhood we may recall that this overlap of dream and waking occurred more easily then, or listening to children we may be reminded how they still blend together in their awareness. As the child grows up, however, a clear distinction between the two is gradually established, until by adulthood it is taken entirely for granted.

A parallel could be drawn here between ontogenetic and phylogenetic development: between the growth of the child to adulthood, and that of our species from prehistory to modern times. Whether considering indigenous peoples as known to us from the recent past, or ancient cultures as they have been studiously reconstructed, we find that the dream world played a major role in their understanding of life. And just as the barrier between dream and waking is very much more porous for children than it is for adults, so also we find a permeability of waking and dream among indigenous peoples when compared to civilised man, or among ancient cultures when compared to modern ones.

Just as the barrier between dream and waking is very much more porous for children than it is for adults, so also we find a permeability of waking and dream among indigenous peoples when compared to civilised man, or among ancient cultures when compared to modern ones.

For the indigene as for the ancient, dreams play a role in two interrelated ways. First, they are thought to have a direct bearing on how events will unfold in waking life, and second, a correct interpretation of the dream will help the one who has received it to avoid negative outcomes and promote positive ones. This understanding has been observed wherever indigenous cultures have been studied; we might take as an example the work of the Catalan anthropologist Josep Mª Fericgla, who lived with the Shuar tribes of Amazonia over the course of the 1990s, when their ancestral way of life, at least in the more remote areas, was still largely intact.

Among the Shuar, Fericgla tells us, the custom is for the whole family group that inhabits a jea (a shack or cabin) to get together around the domestic fire in the early hours of the morning. “They usually wake up before dawn, around 4 or 5 in the morning or even earlier. While waiting for first light to start the morning’s tasks (bathing in the nearby river, going out hunting in the case of the men, or collecting fruits and roots in the case of the women) the family group spends from one to two hours around the fire that the women have revived, in attitudes of quiet absorption as they stir and stretch themselves. The Shuar awaken slowly, like Nature itself, and take a long time to get going.”

It is during this period between sleep and waking, concurrent with the transition from night to day, that the Shuar dwell upon and share their dreams, or withhold them, as the case may be, for their own personal consideration. This is felt to be an activity of vital importance to their individual and collective well-being. The difference with us is evident: even if we did attach significance to our dreams we would rarely have time to ponder on them, alone or together with others, woken as we are by alarm clocks to rise and stumble into the sequences of waking life.

Important for the Shuar, Fericgla tells us, is the concept of “being complete”. Should they suffer lack in any way, their first recourse is to consult their dream life, or else to consume entheogens such as Ayahuasca or Brugmansia, understood as keys of access to a larger reality. “Natural dreams and the visions induced by the consumption of psychotropic substances - and in the Shuar language there is no linguistic or conceptual distinction between these two forms of inner vision - give everything needed to a human being to live in plenitude…”

In common with most indigenous and ancient peoples, the Shuar draw a distinction between “big dreams” and dreams of lesser import. Big dreams are likely to have a major bearing on the life of the dreamer and even on the welfare of the collective to which he belongs. Dreams of this kind, however, can be dreamt only by those who are endowed with inner strength and courage, kákaram, such people being held accordingly in high esteem by the rest of the family group, and even beyond them by the tribe as a whole.

Turning to ancient societies which already had more developed social structures than these Amazonian tribes, we also find a special role for “big dreams”. However these now are more likely to come to the ruler, their interpretation being then entrusted to a priest, sage or prophet. In Book II of The Iliad, for example, Zeus sends down a dream to Agamemnon, lord of the Greek hosts ranged before the walls of Troy. Agamemnon presumes to interpret the dream for himself, foolishly, because the message which it conveys is deliberately deceptive, telling him what he wants to hear rather than what would be in his own best interests. Prompted by the dream he orders a frontal attack on Troy, with dire consequences for his army.

The Pharaoh of Egypt has better luck with his dream of the seven fat and the seven lean kine, as recounted in Genesis 41, for he finds in one of his lowly Hebrew subjects, Joseph the son of Jacob, a true and wise interpreter. As a result the land he rules is able to store up supplies during seven years of plenty, so it can survive the seven years of dearth which the imagery of the dream had indicated would follow on from them.

There are countless similar examples scattered throughout ancient literature. Taken together the picture that emerges is of a dreamworld which exerts a considerable if mysterious sway over waking life. In particular those dreams recognised as major are credited with predicting events if not actually bringing them about. For that matter, there is generally no clear distinction drawn between predicting something and making it happen.

This is why any projection of intent, whether through images as in the case of dreams, or verbally as with blessings and curses, is felt to have operative power. This can be so because for primitive mentality words are felt to be living entities, at least when uttered gravely and in earnest, and in this respect are similar to the potency of the images that come to us in dreams. In either case they are treated lightly at one’s peril.

2

Clearly then dreams are valued quite differently by primitive man when compared to his modern counterpart. Dreams for us may be accorded some value so far as our inner psychological workings are concerned, but it would hardly occur to us to orientate our lives by them, even supposing we could interpret them reliably in the first place. And in any case our cultural assumption is that dreams are a psychic product arising out of past experience, and hence can cast light only on the past - and on the past only of the individual dreamer. Primitive mentality holds just the opposite view, believing that dreams are indicative primarily of the future, although they can also alert us to aspects of the past or present of which we are currently unaware.

Each view of the matter is consistent in its own way. If dreams are the product purely of one’s own psyche, how indeed could they tell us about future events which lie well beyond the scope of personal psychology? If by contrast they arise from a realm that is larger and more numinous than our own, and are endowed with a view that reaches beyond our own limited vision, why should they not be able to foreshadow what may yet come to pass?

For primitive mentality words are felt to be living entities, at least when uttered gravely and in earnest, and in this respect are similar to the potency of the images that come to us in dreams. In either case they are treated lightly at one’s peril.

Parallel with this distinction and reinforcing it is the fact that dreams for primitive mentality are living entities in their own right, whereas for us they are merely the products - or even less, the haphazard byproducts - of subjective psychic processes. This sense is already clearly evident in the episode from The Iliad mentioned above, where the dream as a living entity acts as a messenger attentive to Zeus’s instructions. Moreover it is a dream with a bad character, an oulos oneire, evil or malevolent, so it is well fitted to its deceptive task.

Even with us, however, there may be occasions when a nocturnal visitation seems likewise to convey a message to us from another realm, particularly when it is borne by someone recognized as dead so far as our waking life is concerned. This may be evidence of an archaic mode of thought showing through, having found in dream an opportunity to do so which is denied to it by the waking mind. But equally we might relate this regressive tendency to a revival within us of an outlook arising out of our own childhood. In his discussion of children’s dreams, the great pioneer of developmental psychology Jean Piaget makes just this point. Children, he tells us, initially take dreams to be realities that come to them “from outside”, and only slowly learn to accept the “correct” view that they are generated purely by internal psychological processes.

“To all appearances, the first time that a child has dreams, he confounds them with reality. On waking, the dream continues to be taken for real, as objective, and especially the recollections of the dream are mixed together with memories from the day before. So far as nightmares are concerned, this all seems clear enough. We know how difficult it can often be to calm a child who has come out of a nightmare, and the impossibility encountered in taking away his belief in the dreamed-of objects. …[E]motionally charged dreams, in particular, have a tendency to be completely confounded with the real.”

Something very similar can be seen in the case of a child who has been frightened by, for example, a scary movie, and who subsequently looks under the bed to ensure that no evil personage escaped from it is lurking there. Just as in the case of dreams, the distinction between two orders of reality which for the adult are quite distinct has not yet been firmly established, and so there is a fear-driven overspill from one domain to the other. For that matter even an adult waking up from a nightmare may experience its lingering after-effect, feeling it not merely as something generated by his own psyche, but as an externalised quality of unease inhabiting the darkness of the bedroom. And so the rational mind may need some time to reimpose its own order of reality before the person thus affected can get back to sleep.

Dreams then provide scope for a mode of perception which in the waking life of the adult has long been superseded. This is a point made by Sigmund Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams, the seminal work which paved the way for the modern exploration of man’s unconscious mind. Freud argues that “dreaming is on the whole an example of regression to the dreamer’s earliest condition, a revival of his childhood, of the instinctual impulses which dominated it and of the methods of expression which were then available to him. Behind this childhood of the individual we are promised a picture of a phylogenetic childhood – a picture of the development of the human race, of which the individual’s development is in fact an abbreviated recapitulation influenced by the chance circumstances of life. We can guess how much to the point is Nietzsche’s assertion that in dreams ‘some primaeval relic of humanity is at work which we can now scarcely reach any longer by a direct path’; and we may expect that the analysis of dreams will lead us to a knowledge of man’s archaic heritage, of what is psychically innate in him.”

3

To summarise the foregoing, we can say that for the child, the dreamer and the primitive there is a certain blending and overlapping of states which for us in our waking condition are clearly distinct from each other. For children, as we have seen, dream and waking are not easily distinguished at first, which strikes us as very naive, until we reflect that we as adults take our own dreams to be perfectly real for as long as we are having them. As for the primitive, only a thin veil separates for him the domain of daylight from the kindred realm of night.

In this respect the contrast with modern man is striking, for the world he inhabits, at least again in his waking hours, is a stand-alone reality based on reliable parameters of time and space. These are undergirded by a stable sense of materiality, and by processes of cause and effect which are demonstrable and reproducible. If in a dream I walk down a street and then decide to walk back again, it is rather unlikely that I will find the same surroundings on my return as on my outward journey. If however I were to do the same thing in waking life and find, on retracing my steps, that the street had already changed its aspect, I would surely fear that I was losing my mind.

Here indeed we have a reminder of the similarity between mental illness and the dream state so far as the mutability of our perceptions is concerned. Indeed it was just this parallel between the two phenomena that set Freud off on the quest that would lead eventually to his development of psychoanalysis.

For the child, the dreamer and the primitive there is a certain blending and overlapping of states which for us in our waking condition are clearly distinct from each other.

No doubt we are glad for the stability of our waking perceptions, and yet there is a price to be paid for it, since the resulting world of daytime is decidedly less magical than that of dream. To that extent this stand-alone reality of ours represents a contraction as well as an expansion. There is contraction because our experience has grown impermeable to other realms; yet since we have come to believe that this reality of ours is alone the true one, we will not be inclined to feel any great sense of loss on that account. Instead those lost realms will be seen as doubtful at best from our daytime perspective, if not altogether illusory.

By contrast the expansion represented by this world is indisputable, for it has encompassed the whole Earth, and has pierced its crust and explored the immediate reaches of Space above it. And furthermore we know and understand how all this has come about, because we can cast our gaze back over our whole development and see how the world we inhabit, the real world, has come into being over the course of that same linear time which governs our present-day existence.

Or rather, we would be able to cast our gaze back if only the past didn’t become at a certain point “shrouded in myth”. That phrase has become almost a cliché when speaking of ancient times, suggesting as it does a visible terrain traceable backwards, only at a certain point to be covered over by the fog of legend and fabulation. What a pity, we think! Why couldn’t our ancestors simply tell things straight, the way they really were, rather than getting caught up in such obfuscating flights of fancy?

But how much of this standard response is really just a projection of our present outlook back into the past? For evidently our assumption is that a clearing of the mythic fog would reveal an underlying terrain whose basic parameters were pretty much like our own. Hardly does it occur to us to suppose that those remote times were more elusive because in their very nature they were more uncertain, mutable and dreamlike than the reality which we now call our own.

4

Let us go back to the diurnal passage from dream to waking and ask ourselves, what if man’s emergence out of mythic existence represented something similar on a collective scale? Notice that in both cases the transition is felt to be complete on our arrival at what we have learned to call objective reality. The diurnal version of objective reality is what we call the waking state, while in historical terms, after much tortuous progress, that same quality comes to express itself in the “broad daylight” of scientific modernity. Hence there is a natural affinity between waking consciousness, objective reality and the scientific mindset, just as there is on the other side between myth, dream and the impenetrable domain of night.

We have become familiar through depth psychology with the idea that dreams - some dreams at least, big dreams certainly - can be informed by deep mythic structures still operative in the recesses of the psyche. Freud’s concept of the Oedipus Complex is a notable case in point, even if the founder of psychoanalysis did not lean so much on the parallel between myth and dream as did Carl Jung, his sometime disciple.

Joseph Campbell encapsulates the analogy in the following terms: “Dream is the personalised myth, myth the depersonalised dream; both myth and dream are symbolic in the same general way of the dynamics of the psyche. But in the dream the forms are quirked by the peculiar troubles of the dreamer, whereas in myth the problems and solutions shown are directly valid for all mankind.”

It hardly occurs to us that the remote past might be elusive because in its very nature it was more uncertain, mutable and dreamlike than the seemingly stable and law-governed reality which we now call our own.

So much for the mythic character of our most significant dreams. But if such dreams are informed in their inscrutable imagery by mythic sources, why shouldn’t the converse also hold? Why shouldn’t we expect the remote epoch of mythic consciousness to be imbued with a thoroughly dreamlike character? If such were the case then those times would not have been “shrouded in myth”, as we generally understand that phrase; they would not have had a substrate just like our own only befogged by overactive imaginations. Instead the ground of reality itself would have been different from ours, subtly yet decisively so, as different from our contemporary world as our night dreams are from our daytime existences.

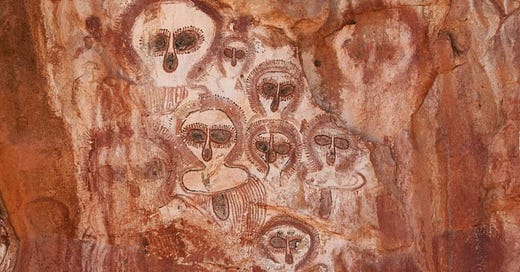

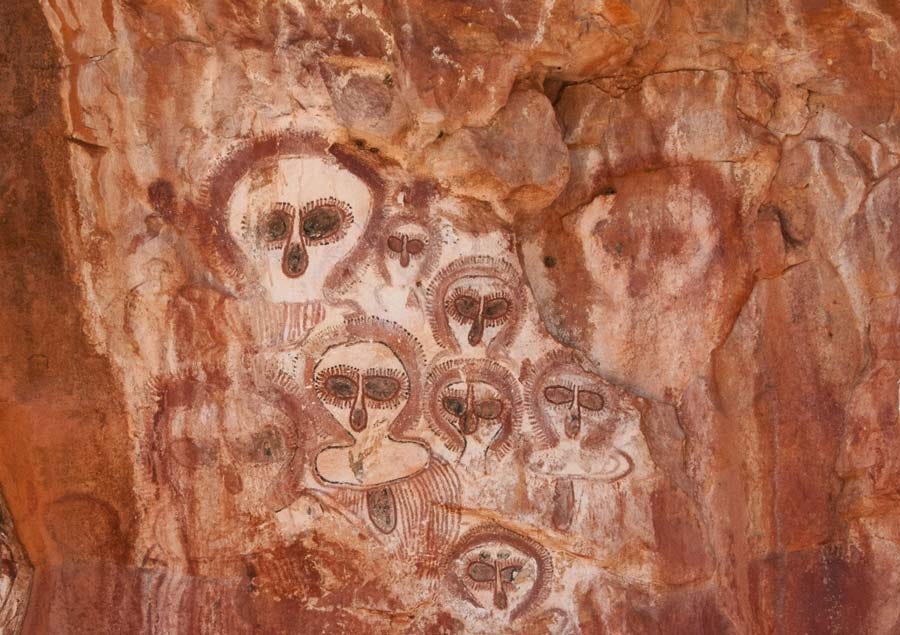

Such a view is implicit in all of myth, but it becomes quite explicit in what is possibly the oldest expression of that ancient form of consciousness to have survived into our own times, which is that of the Australian Aborigines. For them the present world emerged out of a primeval Dreamtime which was latent with potentialities waiting to be awakened into distinctive existence. It was a world that drew forth mythic beings and deities who were the forerunners of humans as we know them today. The role of such beings was to humanise the natural environment, making it habitable for the Aboriginal tribes that would come to dwell in those landscapes.

Having done their work these mythic deities withdrew into the Earth or back up into the Heavens, yet their continued presence remains implicit in the familiar contours of the land and in the changing aspect of the starry sky. Thus the mythic dimension continues to exist for Aboriginal consciousness in and as the Dreaming, receded now from waking existence and yet very much present still on its liminal reaches, in much the way that our dreams are present to waking life, if only we could recall them…

Consider finally the possibility that what we call objective reality not only arose out of a kind of dream state but was destined to descend back into one when its lease of vitality was exhausted. What if that descent were already on our horizon as an imminent prospect? Suppose furthermore that our seemingly stable and objective daytime world were no more than an interval between two darknesses? In such a case there would lie behind us a nocturnal experience where dream and myth intermingled, while before us would loom a brief but febrile hypnagogia that heralded night, dream and unconsciousness once more.

I will be exploring just such a possibility in the second part of this two-part post.